Over the holiday break I was working at a cafe, and was shocked to find the upholstery besprinkled with bones. Looking at this seatback, can you tell what kinds of bones, and from whom, adorn this food establishment?

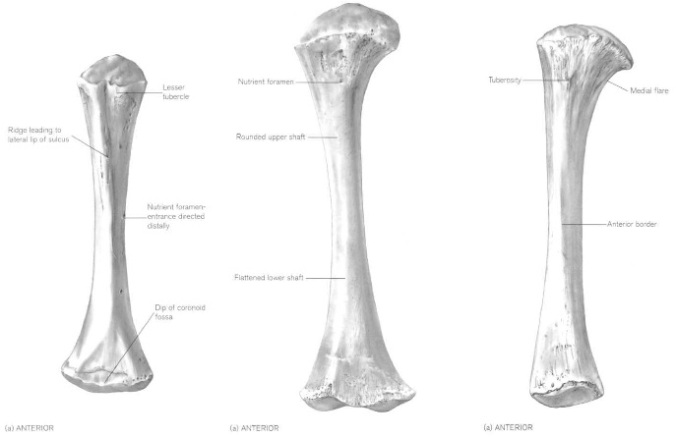

Of course there’s no one right answer, but what I saw were the undeveloped shafts of infant limbs. Infants?! Mildly morbid, mayhap, but one of the distinguishing features of juvenile limb bones compared with adults is that babies’ epiphyses (joint ends) are not fused to the shafts. Observe:

Each of the newborn bones pictured above is comprised of a shaft (diaphysis) that flares proximally and distally into a ‘metaphysis.’ In adults, the epiphyses are completely fused to the metaphyses, but in juveniles the epiphyses are separated from metaphyses by a growth plate made of cartilage. Different epiphyses tend to fuse at characteristic ages, and when fusion occurs bone growth ceases.

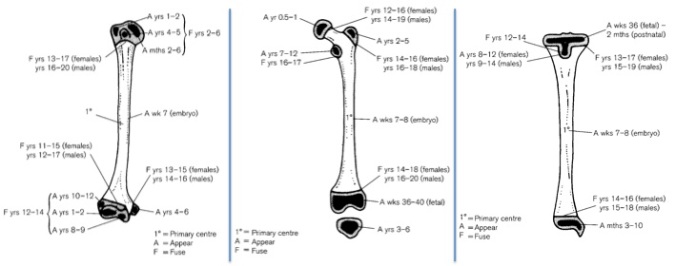

Functionally, this cartilage growth plate allows the bones to increase in length, as multiplying cartilage cells are replaced by bone cells. Because the epiphyses of different limbs fuse at different times, this means that limb proportions change subtly over the course of growth. Practically, this means that if an archaeologist (or forensic scientist or paleontologist) finds a limb shaft with unfused ends, he or she can estimate the age at which the individual may have died:

Standards for epiphyseal fusion. Same bones in same order as in previous figure (also from Scheuer and Black, 2000). “A” refers to the age (years) when the epiphysis firsts appears, and “F” to when it fuses to the shaft.

So if we assume the bones in the second figure are from the same person, we see a humerus, femur and tibia with completely unfused epiphyses. If we refer to our aging standards (third figure), we can see that the first epiphysis to fuse is the proximal humerus, between 2-6 years, and the next epiphyses to fuse are the distal humerus and femur head/proximal tibia between 12-14 years. So we could conclude that this poor kid was certainly younger than 12, years, if not even younger than 2 years. Again, having more of the skeleton (especially jaws with developing teeth) would help us make a more precise estimation.

Baby bones all over the place?! Shame on you, Panera.

GET THIS BOOK: Scheuer L and Black S. 2000. Juvenile Developmental Osteology. Academic Press.

I was thinking frogs. Their double-barrelled ends give them that sort of splayed shape.

Pingback: Driving nails into the 2014 Lawn Chair | Lawn Chair Anthropology