The Human Evolution and Development (HEAD) Lab at Vassar College specializes in virtual, computer-based methods to study bones and fossils and investigate how we became human. Evolution and development provide the theoretical and conceptual framework uniting the major project themes described below. See the Publications page for the original research papers.

Brains

The brain provides the physical machinery necessary for human culture, and cultural behavior is required to obtain the energy our brains and bodies need. Because actual brains do not fossilize, the HEAD Lab uses endocasts to study variation in brain size and shape in humans, fossil hominins, and other primates. My earlier research showed how humans’ unique pattern of brain size growth changed over the course of evolution. More recent projects from the HEAD Lab have used virtual methods to extract information from fragmentary fossil endocasts, from Australopithecus to Neandertals.

Homo naledi

In 2013 a new species of fossil human, Homo naledi, was discovered in a cave site in South Africa. Over 2000 fragmentary fossils revealed a species with the brain size and overall appearance most similar to fossil humans from around two million years ago, but in a species that lived alongside modern humans’ ancestors some 300,000 years ago. Work in the HEAD Lab has helped reveal the biology of this surprising human relative. Homo naledi shared with modern humans a sequence of tooth emergence that has been associated with slow growth and life history. In contrast to this similarity with humans, the Homo naledi hip bone was shaped more like that of Australopithecus even from a young age. Ongoing Homo naledi projects in the lab examine inner ears, brains, and the evolution of infancy.

Gibbons

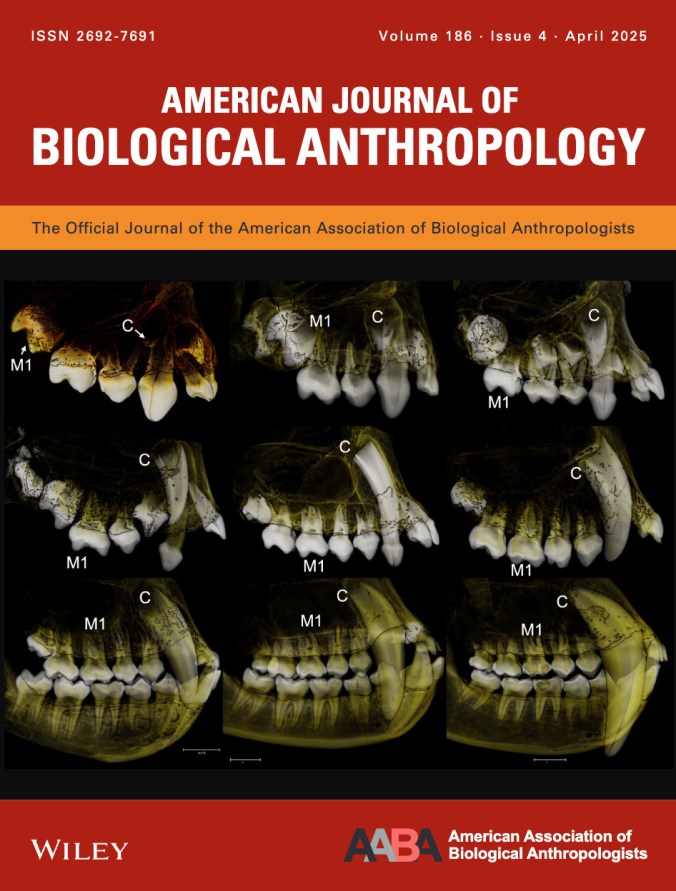

Homo naledi and other recent fossil discoveries show that there were many ways to be human until around 40,000 years ago. The low level of species diversity in humans and the other great apes leaves us without a model for how brains and bodies might vary across closely related species at different timescales. In contrast, today there are about 20 species of gibbons, the small-bodied “lesser apes” distributed across Southeast Asia. The HEAD Lab has begun to study gibbon skulls from museum collections, to expand on the idea of a gibbon model for understanding brain variation among fossil humans. A pilot study (here) showed how brain shape differs among the four main groups of gibbons, while a unique microCT dataset is the basis for several projects investigating how the skull, brain, and teeth develop.