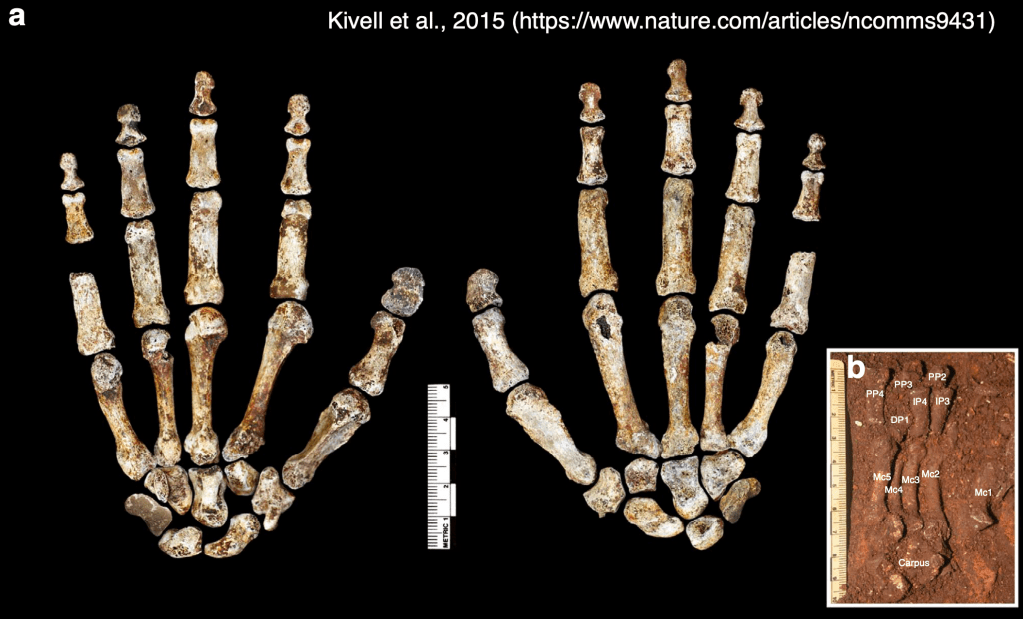

Homo naledi is one of my favorite extinct humans, in part because its impressive fossil record provides rare insights into patterns and process of growth and development. When researchers began recovering naledi fossils from Rising Star Cave 10 years ago, one of the coolest finds was this nearly complete hand skeleton. The individual bones were still articulated practically as they were in life so we know which bones belong to which fingers, allowing us grasp how dextrous this ancient human was. And since finger proportions are established before birth during embryonic development, we can see if Homo naledi bodies were assembled in ways more like us or other apes.

In a paper hot off the press (here), I teamed up with Dr. Tracy Kivell to analyze finger lengths of Homo naledi from the perspective of developmental biology. On the one hand, repeating structures such as teeth or the bones of a finger must be coordinated in their development, and scientists way smarter than me have come up with mathematical models predicting the relative sizes of these structures (for instance, teeth, digits, and more). On the other hand, the relative lengths of the second and fourth digits (pointer and ring fingers, respectively) are influenced by exposure to sex hormones during a narrow window in embryonic development: this ‘digit ratio’ tends to differ between mammalian males and females, and between primate species with different social systems.

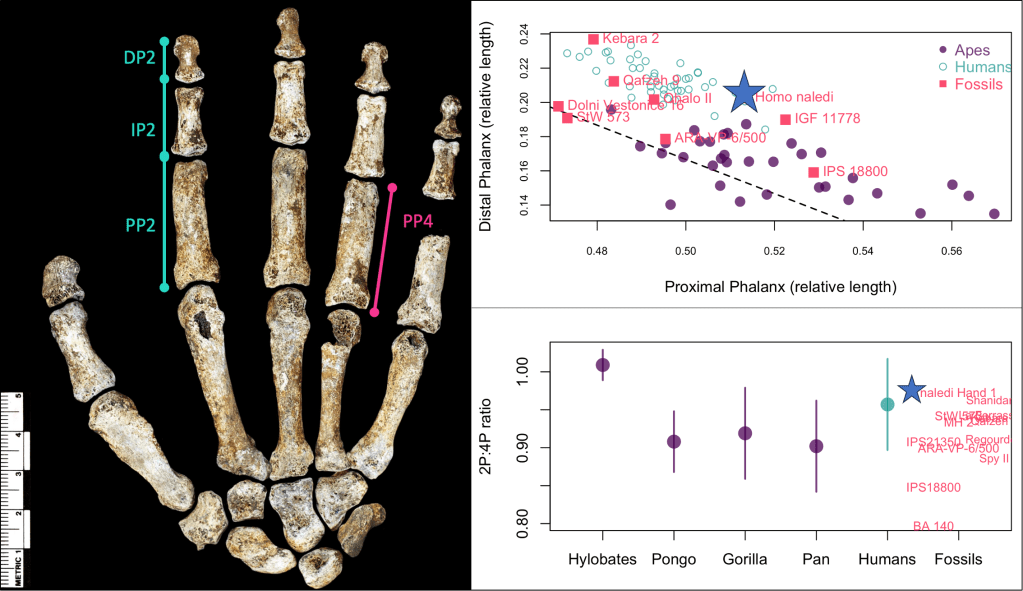

So, Tracy and I examined the lengths of the three bones within the second digit (PP2, IP2, DP2) and of the first segment of the second and fourth digits (2P:4P) in Homo naledi, compared to published data for living and fossil primates (here and here). What did we find out?

The first graph above compares the relative length of the first and last segments of the pointer finger across humans, apes, and fossil species. The dashed line shows where the data points are predicted to fall based on a theoretical model of development. There is a general separation between humans and the apes reflecting the fact that humans have a relatively long distal segment, which is important for precise grips when manipulating small objects. Fossil apes from millions of years ago and the 4.4 million year old hominin Ardipithecus are more like apes, while Homo naledi and more recent hominins are more like modern humans. Because both humans and apes fall close to the model predictions, this means the theoretical model does a good job of explaining how fingers develop. Because humans and apes differ from one another, this suggests a subtle ‘tweak’ to embryonic development may underlie the evolution of a precision grip in the human lineage, and that it occurred between the appearance of Ardipithecus and Homo.

The second graph compares the ‘digit ratio’ of the pointer and ring fingers from a handful of fossils with published ratios for humans and the other apes. Importantly, the digit ratio is high in gibbons (Hylobates) which usually form monogamous pair bonds, while the great apes (Pongo, Gorilla, Pan) are characterized by greater aggression and mating competition and have correspondingly lower digit ratios. Ever the bad primates, humans fall in between these two extremes. Most fossil apes and hominins have digit ratios within the range of overlap between the ape and human ratios, but Homo naledi has the highest ratio of all fossil hominins known, just above the human average. It has previously been suggested that humans’ higher ratio compared to earlier hominins may result from natural selection favoring less aggression and more cooperation recently in our evolution. If we can really extrapolate from digit proportions to behavior, this could mean Homo naledi was also less aggressive. This is consistent with the absence of healed skull fractures in the vast cranial sample (such skull injuries are common in much of the rest of the human fossil record).

You can see the amazing articulated Homo naledi hand skeleton for yourself on Morphosource. Its completeness reveals how handy Homo naledi was 300,000 years ago, and it can even shed light on the evolution of growth and development (and possibly social behavior) in the human lineage.