I’m writing a review of the “robust” australopithecines, and I’m reminded of how drastically our understanding of these hominins has changed in just the past decade. Functional interpretations of the skull initially led to the common wisdom that these animals ate lots of hard foods, and had the jaws and teeth to cash the checks written by their diets.

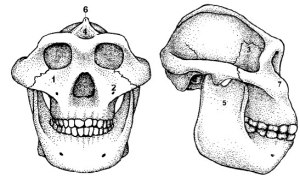

Comparison of a “gracile” (left) and “robust” (right) Australopithecus face, from Robinson (1954).

While anatomy provides evidence of what an animal could have been eating, there is more direct evidence of what animals actually did eat. Microscopic wear on teeth reflects what kinds of things made their way into an animal’s mouth, presumably as food, and so provide a rough idea of what kinds of foods an animal ate in the days before it died. Microwear studies of A. robustus from South Africa had confirmed previous wisdom: larger pits and more wear complexity in A. robustus than in the earlier, “gracile” A. africanus suggested more hard objects in the robust diet (e.g., Scott et al., 2005). A big shock came a mere 8 years ago with microwear data for the East African “hyper robust” A. boisei: molars had many parallel scratches and practically no pitting, suggesting of a highly vegetative diet (Ungar et al. 2008).

Microwear in A. boisei (blue) and A. robustus (red). Although they overlap mostly for anisotropy (y-axis), they are completely distinct for complexity (x-axis). Data from Grine et al. (2012) and skull diagrams from Kimbel et al. (2004).

Stable carbon isotope analysis, which assesses what kinds of plant-stuffs were prominent in the diet when skeletal tissues (e.g. teeth) formed, further showed that the two classically “robust” hominins (and the older, less known A. aethiopicus) ate different foods. Whereas A. robustus had the carbon isotope signature of an ecological generalist, A. boisei had values very similar to gelada monkeys who eat a ton of grass/sedge. GRASS!

Stable carbon isotope data for robust australopithecines. Data from Cerling et al. (2013) and skull diagrams from Kimbel et al. (2004). Note again the complete distinction between A. robustus (red) and A. boisei (blue).

![]() While microwear and isotopes don’t tell us exactly what extinct animals ate, they nevertheless are much more precise than functional anatomy and help narrow down what these animals ate and how they used their environments. This highlights the importance of using multiple lines of evidence (anatomical, microscopic, chemical) to understand life and ecology of our ancient relatives.

While microwear and isotopes don’t tell us exactly what extinct animals ate, they nevertheless are much more precise than functional anatomy and help narrow down what these animals ate and how they used their environments. This highlights the importance of using multiple lines of evidence (anatomical, microscopic, chemical) to understand life and ecology of our ancient relatives.

REFERENCES

Cerling TE, Manthi FK, Mbua EN, Leakey LN, Leakey MG, Leakey RE, Brown FH, Grine FE, Hart JA, Kaleme P, Roche H, Uno KT, & Wood BA (2013). Stable isotope-based diet reconstructions of Turkana Basin hominins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110 (26), 10501-6 PMID: 23733966

Grine FE, Sponheimer M, Ungar PS, Lee-Thorp J, & Teaford MF (2012). Dental microwear and stable isotopes inform the paleoecology of extinct hominins. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 148 (2), 285-317 PMID: 22610903

Kimbel WH, Rak Y, & Johanson DC (2004). The Skull of Australopithecus afarensis. Oxford University Press.

Robinson, J. (1954). Prehominid Dentition and Hominid Evolution Evolution, 8 (4) DOI: 10.2307/2405779

Ungar PS, Grine FE, & Teaford MF (2008). Dental microwear and diet of the Plio-Pleistocene hominin Paranthropus boisei. PloS One, 3 (4) PMID: 18446200