Last month I was flying down to New Orleans for the AAPA conference. I was excited to try authentic beignets & sazeracs, present new research, and catch up with colleagues. Midway through the flight I glanced out the window, not expecting to see much. But lo!

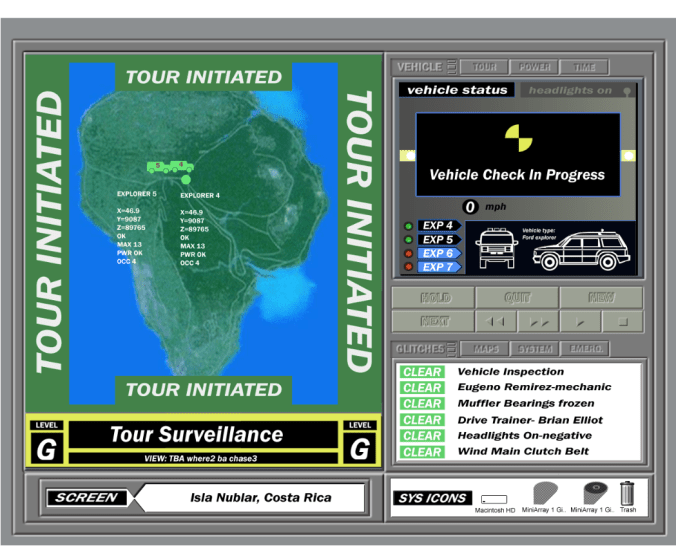

Thankfully there wasn’t something on the wing. But there was something strange out there in the sparkle of sprawling city lights:

What’s that I spy outside the city center?

A bit outside of the main jumble of street lamps appears to be a concentration of light superficially similar to an incus, one of the three auditory ossicles of the middle ear:

Left: An osteologist’s nightmare at 20,000 feet. Right: Ear ossicles from White et al. (2012).

As a good mammal, there are three small bones inside your middle ear. These are fully formed at birth, and help transfer and amplify sound vibrations from your eardrum to your inner ear. It’s nuts. What’s even more nuts is that paleontologists and anatomists have figured out that the tiny, internal incus and malleus of mammals evolved from larger, external pieces of the jaws of our pre-mammalian ancestors. INSANITY!

Cross section of a right ear, viewed from the front. Image credit.

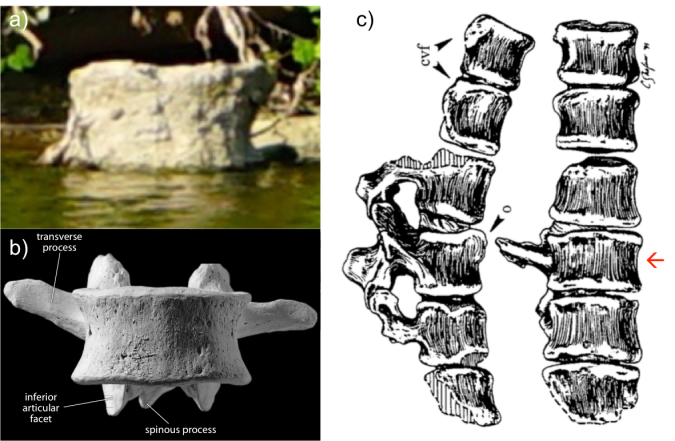

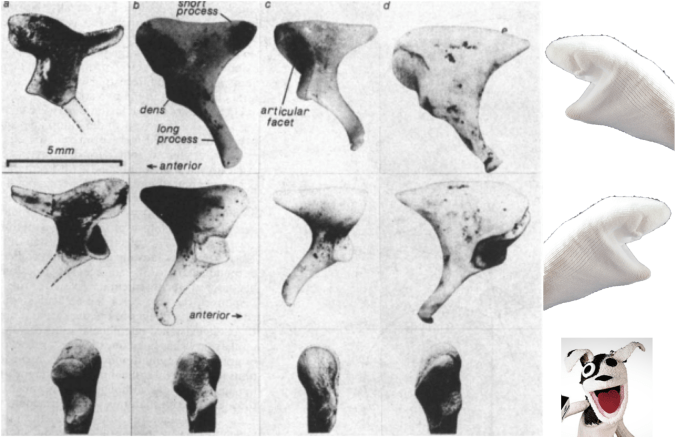

Being so tiny, it’s not surprising that auditory ossicles are not often recovered from skeletal remains, and are pretty rare in the human fossil record. Nevertheless, some are known and their comparison with humans’ ossicles is pretty interesting. The oldest incudes (yes, the plural of incus is incudes) I know of are from SK 848 and SKW 18, Australopithecus robustus fossils from Swartkrans in South Africa (Rak and Clarke, 1979; Quam et al., 2013). SK 848 is on the left in the set of images below:

Incus bones in three different views of SK 848, human chimpanzee, gorilla, sock puppet (left to right). Modified from Rak and Clarke, 1979.

SK 848 to differs from humans and African apes in looking more like a screaming sock puppet with a horn on the back of its head. Additional ossicles are known from South African australopithecines, including the older A. africanus from Sterkfontein (Quam et al., 2013). Interestingly, malleus of these hominins is very similar to that of humans, and Quam et al. (2013) think this ossicle may be one of the first bones in the entire skeleton to take on a human-like configuration during hominin evolution. Functionally, this may mean that the frequency range to which human ears are adapted may have appeared pretty early in our lineage as well (Quam et al., 2015).

Who’d’ve thunk we’d learn so much just from looking out an airplane window?

Read more!

Read more!

Quam, R., de Ruiter, D., Masali, M., Arsuaga, J., Martinez, I., & Moggi-Cecchi, J. (2013). Early hominin auditory ossicles from South Africa Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110 (22), 8847-8851 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1303375110

Quam, R., Martinez, I., Rosa, M., Bonmati, A., Lorenzo, C., de Ruiter, D., Moggi-Cecchi, J., Conde Valverde, M., Jarabo, P., Menter, C., Thackeray, J., & Arsuaga, J. (2015). Early hominin auditory capacities Science Advances, 1 (8) DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500355

Rak Y, & Clarke RJ (1979). Ear ossicle of australopithecus robustus. Nature, 279 (5708), 62-3 PMID: 377094